The Loyalist

In the middle of the night of May 21, 1780, with the American Revolutionary War in its sixth bloody year, there came a loud rapping at the old Sussex County Courthouse door, waking the sheriff. The sheriff opened a second floor window and demanded to know the business of those who woke him. A man's voice out of the darkness told him that they were patriots and had a loyalist prisoner for him — indeed, one of the cohorts of the infamous James Moody. The sheriff was delighted. Moody was known to be in the vicinity, raiding homes and capturing “rebels,” and had even recently plotted to kidnap New Jersey's patriot Gov. Robert Livingston in Morris Town. Continental authorities were eager to stop him. The voice in the dark called on the sheriff to come down and open the door.

But the sheriff refused. He said he had orders, since Moody and his raiders were about, not to open the court house after sunset. He told the man he'd take his captive from him in the morning.

At that point, James Moody — for it was none other — dropped the pretense and shouted sternly:

“The man who now speaks to you is Moody. I have a strong party with me. And if you do not this moment deliver up your keys, I will instantly pull this house down about your ears!”

The alarmed sheriff withdrew from the window without surrendering the keys. The “strong party” with Moody was six other loyalists. But Moody and his men were clever fighters who knew how to utilize terror. Before the sheriff could attempt to get any assistance from townspeople, the raiders started whooping loudly like Indians on the warpath. The inhabitants of New Town — 20 to 30 households — panicked, fearing hostile Indians at least as much as British soldiers, and fled their poorly protected homes for safety in the woods.

Moody, meanwhile, broke through a casement window, found the sheriff, got the keys, freed eight loyalist prisoners and disappeared in the dark. The local militia soon gave chase. They recovered four escaped prisoners. But the others, including Moody, got away.

He almost always did.

Photo: joseph picard Moody marker, Sparta

The man George Washington dubbed “that villain Moody” and New Jersey's loyalist Gov. William Franklin called “the best Partizan we had,” was born an American in 1744, in Little Egg Harbor in what is now Ocean County. He married and moved to a 500-acre farm owned by his father in Knowlton, when it was still part of Sussex County. The “best climate and happiest country in the world,” is how he described his environs. After “the shot heard 'round the world” at Lexington in 1775, Moody remained loyal to Britain.

According to his own account, A Narrative of the Exertions and Sufferings of Lt. James Moody — which he wrote after the war to convince British authorities to compensate him for the loss of his property and his many efforts for the Crown — he considered rebellion tantamount to treason.

“However real and great the grievances of the Americans might be,” he said, “rebellion was not the way to redress them.”

But he did not, at first, take up arms against his militant neighbors. Instead, he tried to go on peacefully with farming life, while the surrounding world was boiling over.

He was walking in a field in 1777 with another farmer when a militia unit marched up the road, recognized the loyalists and fired on them. Moody got away. He allied with other loyalists, abandoned his homestead and fled with about 70 other men for the British lines on Staten Island.

Again and again, over the next four years, Moody returned to New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania, raiding rebel homesteads, skirmishing with troops and militia, recruiting soldiers for the British forces and, most remarkably, infiltrating units of the Continental Army to spy on the enemy, measure troop strength and supply status, and steal documents, including battle plans and George Washington's mail many times, “almost at will,” as a leading historian of that war's espionage put it. Gov. Livingston put a price on his head. Many times they were close to taking him, or killing him. Again and again, he got away.

He knew well the woods of Sussex County and his favorite hideout was in what we now call the Muckshaw Ponds Preserve in Andover and Fredon. It is easy to see how someone — to say nothing of seasoned woodsmen and soldiers — could hide back there. Even today, with a marked trail (starting on Fredon Springdale Road) and a map by the Nature Conservancy, it is difficult terrain to negotiate, a veritable thick green jungle with hardscrabble ridges, swampy, pest-infested lowlands and a deer path for trail. Moody's Rock, the name given to the rock formation and cave system he and his men used, is deep within these woods. Because of his success, British authorities supplied Moody with gold coin to enhance recruiting efforts. Legends have therefore emerged that the gold is still buried at Moody's Rock or somewhere else in Muckshaw. If so, it will probably stay where it is.

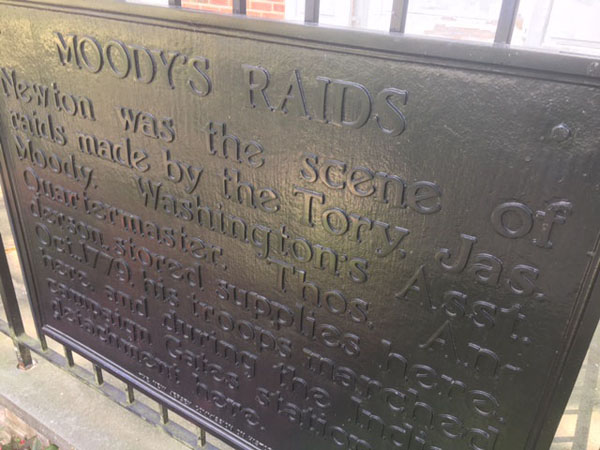

Photo: joseph picard Marker at Dennis Library, Newton

Moody also knew which farmsteads housed loyalist sympathizers and was able to serpentine through the region, finding sufficient shelter and food to sustain his enterprises and escapes. It was when returning to British lines in July 1780, two months after the raid on the county jail, that he was at last captured. He was arriving at the British fort at Bull's Ferry on the Hudson, just north of Weehawken, when that fort came under attack by an American army under Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Moody was taken, hauled up to West Point and shackled in a cell.

He was brought back to New Jersey to be hanged in Washington's camp, when he again escaped. He somehow broke the bolt on his iron manacles, knocked out a sentry, took the man's musket and, instead of running into the woods, stood at post like a sentry. When shortly afterwards, the hue and cry went up that Moody had escaped and armed troops proceeded to look for him, Moody joined his own pursuers, until he could part from them and make his way back to the British.

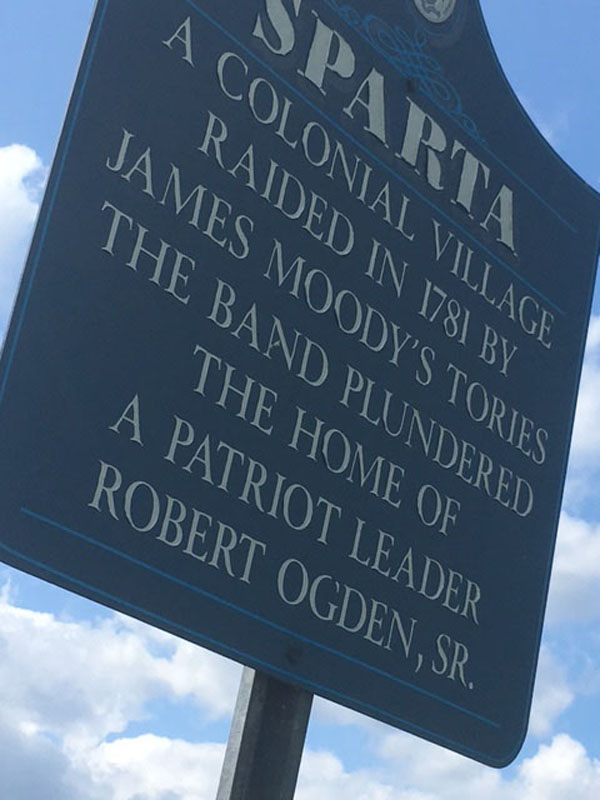

He went right back to stealing Washington's mail and other exploits. One, in 1781, was raiding and plundering the home of Robert Ogden, Sr., a patriot and a founder of the village of Sparta, whose family later gave its name to Ogdensburg. A marker on the grounds of the VFW building on Main St. in Sparta records the event of Moody's raid.

His last major adventure occurred later that year, when he, his brother and another loyalist attempted to steal the foundation documents of the Revolution from a government office in Philadelphia. The plot turned out to be a trap. Moody's brother John and the other man were captured. Moody escaped again, but barely, hiding in a haystack for two days, before stealing a boat and paddling up the Delaware. When he got back to British lines, he learned that his brother had been executed as a spy.

In October, 1781, the British army under Lord Cornwallis surrendered to the allied armies of Americans under Washington and French under Rochambeau at Yorktown, Virginia, effectively ending the war. In 1782, while the combatant nations were negotiating peace terms, Moody managed his last escape. He sailed to England, where the Crown eventually compensated him for his losses and his work. Moody returned to North America and became a ship builder in Nova Scotia. In case anyone might wonder if the American-born fellow experienced a change of heart, Moody's first vessel was christened “The Loyalist.”

image Courtesy of Sussex County Sheriff's Office On the site of the old Sussex County Courthouse on High Street in Newton, the older, original Sussex County Courthouse once stood, from 1761 to 1847, when it was gutted by fire. It was a two-story stone building that housed the court, the sheriff's office and living quarters and, on the lower floor, the county jail.