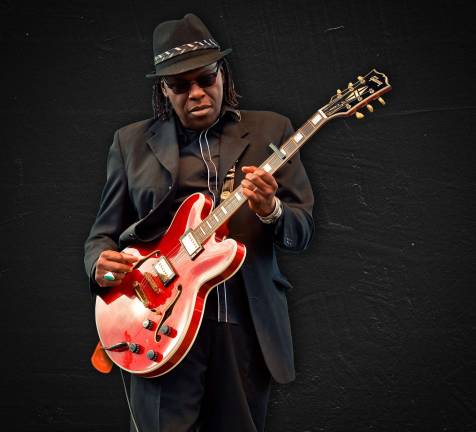

Bluesman at the Stanhope House

By Joseph Picard

Stanhope — Joe Louis Walker is a bluesman — a guitarist, singer and songwriter with a half-century of performing experience. While unique and innovative in style, his music is steeped in blues tradition and his respect is strong and loving for the artists whose lives and work created that tradition.

“The blues is about these artists expressing themselves, expressing their suffering through the music,” Walker said in a recent interview with Straus News. “For me, this music is always inspirational.”

The blues was born in the American South from the hearts, hands and voices of slaves and the children of slaves, who made music to lighten each other’s load. The blues came north when the post-slavery black population did, to Memphis, Kansas City, Chicago, New York and elsewhere, and continued to reflect the black experience, and to attract an expanding audience. The blues has since gone around the world, and has heavily influenced American music and American culture.

Take, for example, the unmistakable message of the 1977 song by Muddy Waters: “The blues had a baby and they called it rock and roll.”

In the 1950’s and 1960’s Americans fell in love with rock and roll and the blues. But a large portion of American society was not enamored of the black artists who were creating the vibrant and poignant music. Songs like “Hound Dog” by Big Mama Thornton and “Tutti Frutti” by Little Ricard were covered on major labels by white artists Elvis Presley and Pat Boone, played on major radio stations and became monster hits. In these and many other cases, neither the credit nor the profit went to the original artists.

“I think America likes to see itself in the mirror,” said Walker, a member of the Blues Hall of Fame, who will be performing at the Stanhope House in Stanhope on Dec. 7. “If you are going to appropriate someone’s music, you should at least have the decency to credit them.”

Walker was born in 1949 in San Francisco.

“In that same year B.B. King had a hit record,” he said. “But he could not eat at the same lunch counter, or get gas at the same gas station, or use the same restroom. The things that people like B.B. King, Muddy Waters and others had to go through — it’s all there in their music. They’ve turned the suffering they experienced into music. It’s heartfelt and it’s personal. The blues is the expression of the artist’s suffering.”

Walker’s family was made up of music lovers. His father listened to numerous blues artists, including Sonny Boy Williamson and Pete Johnson. His mother was a big fan of B.B. King.

“When I was a good boy, they’d let me listen,” Walker said. “My brothers and sisters were into rock and roll. So, I heard a lot of different music. I gravitated to the blues.”

Walker became a young guitar phenom in the Bay Area. In his teens he played with the likes of John Lee Hooker, Buddy Miles, Thelonious Monk, Willie Dixon, John Mayall and Muddy Waters. He traveled to the East coast and became close friends with white, Chicago-born blues guitar legend Michael Bloomfield.

Walker said that, unlike many talented rock and rollers, Bloomfield understood and respected the culture and the people the blues came from.

“Mike saw and respected the connection to the older generation of blues artists,” Walker said. “He immersed himself in the culture, related to the suffering that produced the blues. Mike would say ‘I didn’t invent this. These are the guys who invented this.’”

Not every blues-appropriating band of the era showed such a level of respect. In 1987, to cite a prominent example, the English band Led Zeppelin reached an out-of-court settlement with Willie Dixon over Zeppelin’s 1969 mega-hit “Whole Lotta Love,” which, with a few words changed, sounds just like the 1962 Muddy Waters’ song “You Need Love,” which was written by Dixon. Dixon used the undisclosed amount of cash to finance his organization for protecting musicians’ song rights and royalties. He also finally got credit (along with Led Zeppelin’s four members) as the songwriter.

“There have been appropriations that are note for note,” Walker said. “How can you do something like that? I can’t. How can you take someone else’s music and act like it’s your own? Where is your music? Where are your notes?”

While it concerns Walker that many black musicians have not gotten the credit or the remuneration they deserve, he recognizes that white artists have played a big part in introducing the blues to a wider audience.

“God bless people like Jeff beck and the Rolling Stones for honoring the real bluesmen and bringing them to the attention of more people,” he said. “The Allmans, too. I prefer Sonny Boy Williamson’s ‘One Way Out’ to the Allmans’ cover, but I credit the Allmans for shining a light on blues artists.”

In 1986, Walker released his first solo album, Cold Is the Night. Since then he’s been pumping out close to an album a year, while touring the nation and the world and collaborating on some of the finer blues recordings. In 1993, on B.B. King’s Grammy Award-winning Blues Summit, Walker duets with the late King on “Everybody’s Had the Blues,” a Walker original. In 1994, JLW was released, featuring Walker playing with the likes of James Cotton, Branford Marsalis and Tower of Power. He co-produced three albums with Steve Cropper (of Booker T. & the MGs and The Blues Brothers band). One of these, 1997’s Great Guitars, finds Walker jamming with, among others, Cropper, Bonnie Raitt, Buddy Guy, Taj Mahal, Otis Rush and Ike Turner.

He won the Blues Music Award for Band of the Year in 1996, and for Contemporary Male Artist of the Year in 1988 and 1991. In 2012 he released Hellfire to wide acclaim. Billboard magazine said: “Hellfire is a heavenly showcase for Walker’s virtues.” In 2013, Walker was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame. His current well-received album is Everybody Wants a Piece, and there is another album coming in 2018.

Walker said: “I’d like to be known for the credibility of a lifetime of being true to my music and the blues.”

All signs are that he is fulfilling that desire. His music runs the blues gamut from achingly soulful ballads to gritty, hard-driving declarations. His voice is compelling and his guitar work masterful. He can make that electric ax wail and weep, rip, rage and sweetly sing, and seem to do so effortlessly and with inspiring confidence. On Thursday evening, Dec. 7, Walker will be taking the stage at the Stanhope House, a venue he has played before and one that has been welcoming of traditional blues for many years. Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, John Lee Hooker, Albert King and Buddy Guy, to name a few, have delivered the blues from the Stanhope House stage.

“The business end of performing and recording, that can get to you at times,” said Walker, who resides with his family in upstate New York. “But playing the music, the music is always inspirational. That’s where you get your power. That’s how you know you are connecting with people. That is so refreshing. That’s my wheelhouse. When I’m on stage playing, I feel 10 feet tall.”

“The confidence,” he said, “comes from honest music.”