Heroin in our midst: Part 3

WANTAGE – Heroin doesn’t work—it delivers.

All of the recovering addicts consulted for this series reported the euphoric upsides and the nauseating, paralyzing downsides of the drug.

For Tess, an office worker in her mid-30s, the positives were as strong as they were fleeting.

“The first couple of times I felt like I was getting this huge hug from God. I was being told that everything was going to be alright,” she said. “When I am dealing with years and years worth of depression and anxiety and all these different mental issues, to feel that way in that moment I was like, ‘Ok, this is it.’”

Rachel Wallace, a licensed clinical social worker at the Center for Prevention and Counseling in Newton, said that the extreme highs of heroin and the prolonged lows of heroin withdrawal are well-researched.

“Particularly with opiates, there is a very fast physical dependence and a very quick psychological dependence,” she said.

Beyond the ecstatic experience of the drug, Tess reported a feeling of belonging, even a sense of identity with her early use of heroin.

“From that point, heroin just felt like my drug. Like, ‘Ok. This is me. I don’t care if I’m not around other people doing it or if not or if I’m home stuck by myself. This is my little safety net, my little safety zone,'" she said. "I just felt safe, even though that’s ridiculous because you’re not safe and you could kill yourself at anytime. That’s how I felt.”

The withdrawal sickness that followed was less inviting. "It’s like you become your own nurse,” one recovering user said.

Several addicts described a turning point where the euphoria of the drug is swapped for the feeling of relief that comes from averting withdrawal sickness.

“Withdrawal is significant, uncomfortable,” Wallace said. “Someone in withdrawal from opiates will say that they feel they’re going to die or that they want to die – which drives the use more.”

Tess regularly struggled to get to her job while using. One night the shot she took caused her to faint, a phenomenon heroin users call 'falling out.'

“It happened a couple of times, but I made it into work,” she said.

As Tess’s habit grew, it became harder for her to maintain her job. She even went into debt in order to free up cash for buying heroin, she said.

Addiction and desperation

Some users find legitimate ways to come up with the time and money to support their illegal habits.

But others, like Karly Casson, are not as responsible.

Police found Casson with heroin in Wantage Township last March and arrested her. Six months later, police were called to the A&P supermarket in town, where they found and arrested Casson and an accomplice.

“I filled a shopping cart with baby formula and some cold and flu items and I walked out,” Casson said at her court appearance in April.

Her confession was a part of the process of entering the county’s drug court system, a special probationary court that requires total abstinence and recommends treatment of addicts involved in crimes.

Prosecutors valued the goods Casson took at more than $1,000. Another charge that stemmed from an alleged theft of a family member’s computer was dropped.

As part of her court-ordered treatment, Judge N. Peter Conforti directed Casson to enter an intenstive outpatient program for addiction.

The Center for Prevention takes on many such referrals from drug courts for the outpatient treatment it offers. Last year, the center served more than 450 clients individually and more than 100 others in group sessions.

However, success rates for heroin-dependent clients in intensive outpatient treatment are unclear. The Center for Prevention does not differentiate between alcoholism and heroin dependency when it reports on patient outcomes. Across all addictions, the center's success rate is between 50 and 60 percent, Wallace said.

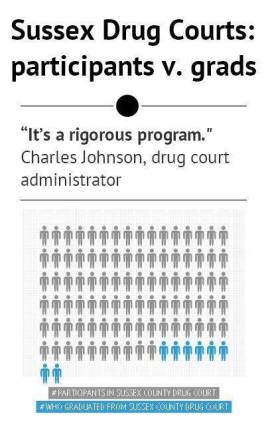

Successful graduates from the drug court are even scarcer. In 2012 there were 98 participants in Sussex County’s drug court, according to the court administrator Charles Johnson. Eight graduated after actively attending drug court for two to three years.

“It’s a rigorous program,” Johnson said.

Unstable recoveries

“Typically with opioid-dependent individuals, there is such devastation, so many legal consequences, their integrity, everything, they are simply outcast, and there aren’t a lot of opportunities,” Wallace said.

Heroin addicts who are on probation and who have lost their licenses can be found in violation if they illegally use a car. In rural areas like Sussex, the lack of a license poses a threat to recovery for those addicts who are trying to stay out of jail as much as they are trying to earn a living, she said.

Also, because withdrawal is so painful, recovering addicts will very often need medical replacement therapies, like methadone and buprenorphine – prescription medications that can help wean an addict off of the drug.

“A lot of people who have crossed into serious heroin-dependence will need long-term, residentially supported detoxification and medically-assisted withdrawal, “ Wallace said.

After one bad night too many, Tess wound up in a residential rehabilitation facility outside the state, where doctors prescribed her suboxone, a prescription replacement drug for heroin users.

But Casson may not be so fortunate. Once in IOP she will be regularly drug tested, but she may not have the wrap-around support of residential treatment, because residential settings like the one Tess found are few and far between in Sussex County.

Instead of entering residential treatment, Casson's attorney explained in court that she planned to live with another drug court participant, Justin Lazier.

Lazier was convicted of DWI and possession of heroin after a motor vehicle stop by police. His driver’s license was revoked as part of his sentence.

As she was being escorted out of the courtroom for her release, the assistant prosecutor handling her case wished Casson well.

“Good luck,” he said.

Heroin in our midst

Part 1: Heroin is here.

Part 2: Law enforcement’s attempt to deal with the problem linked to the deaths of 80 of Sussex County’s sons, daughters, mothers and fathers since 2000

Part 3: Confronting addiction; do drug courts work?

Part 4: The business of hooking kids