An underground look at history

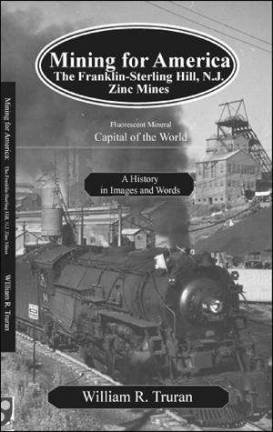

New book chronicles Sussex County’s zinc industry, By Mark J. Yablonsky FRANKLINFirst, it was a pictorial history of “Franklin, Hamburg, Ogdensburg and Hardyston,” then came a similar work about Sparta being the “Head of the Wallkill.” Now, Dr. Bill Truran has literally done underground reporting. Truran, a local historian with deep-rooted family ties to Franklin’s mining past, has come out with his third book in as many years. The recently released 320-page book, however, is much less about towns and much more about the zinc mining industry, both in the legendary Franklin zinc mines and in the mines of Sterling Hill of Ogdensburg. Titled “Mining for America: The Franklin-Sterling Hill, N.J. Zinc Mines,” the book is an impressive chronicle of zinc mining, how and why it was done, and what benefits were derived from it. “It is strictly about mining and there’s so much to tell, that it ended up being 320 pages,” said Truran, who is a professor of project management at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken. “In depicting the mines, I came to the realization that you have to take one step at a time, talking about the history first. “I learned an enormous amount,” Truran continued. “I had much heritage from my family and in talking to others, but in researching further, I learned so much in that there’s a lot to know.” Unlike his initial 2004 book, “Franklin, Hamburg, Ogdensburg and Hardyston,” this new bookas was the case with the 2005 book about Spartawas published by Trupower Press, which is run entirely by Truran himself. His book of two years consisted largely of photographs collected by his late grandfather, who had worked in the Franklin mines from 1912 to 1947, as well as Truran’s father Wilfred, who worked the Franklin mines from 1947 up until its closing on Sept. 30, 1954. The second book was largely the same, but now, like a dentist who drills a tooth on the outsides before heading directly into the center of the cavity, Truran has focused on research into the “dirty, dark and demanding” trade of mining itself. But while the similarities between both the Franklin and Sterling Hill mines are obvious, there are many notable differences as well. In Franklin, mining began with open-cut work in 1854, a strong indication of what was in the ground below. In Sterling Hill, however, Truran has cited circumstantial evidence indicating that the Dutch may have done at least some exploratory work there during the 1600s. Also, the shape of the Franklin ore body resembled an upside-down turkey, or in the author’s view, a canoe “cut in half, with one part diving down at the middle.” The Sterling Hill ore body, however, was shorter across but somewhat deeper. The closings of the two mines, 32 years apart, also had different backgrounds, Truran and others have noted. The Sept. 30, 1954 closing of the Franklin mines had been expected for at least a year in advance; the shutdown of the Sterling Hill mines in March 1986, however, was at least partly the result of a bitter tax dispute between the New Jersey Zinc Co. and the borough of Ogdensburg. “Well, it wasn’t just the tax dispute,” Truran explained. “It was also the fluctuating price of zinc. And the amount of ore they had at the (Ogdensburg) site was less and less, and it was deeper and deeper, so it was getting tougher to mine. The fact that they were so deep was already a downer for them.” Hauntingly, Truran presents a photo of the Palmerton, Pa. Hospital, a virtual exact model of the Franklin Hospital, although the latter was built one year after the former. Palmerton is where smelting plants for the zinc ore were located. Both designed by architects Delano & Aldrich, neither hospital building is in existence today. But the benefits of zinc, while perhaps unbeknownst to many, are very much in effect today. Reproducing some World War Two posters extolling the necessity of buying war bonds, Truran shows that zinc went into products ranging from tires and rubber, to aluminum and plastics and even paint. But the uses of zinc don’t stop there. Some people today even take zinc pills for the purpose of boosting their immune systems. “You should put that in there,” Truran replied. “Because it will let everyone know how important zinc is today in everyday life. If you read the ingredients, you’ll see zinc in there.” Because his grandfather, Sydney Hall, had such a priceless collection of photos, some of them were used for the present book, too. Truran also said a lot of photographs in it came from the Franklin Mineral Museum, located directly across the street from where the open cut mining began 152 years ago. And for geologists and rock collectors alike, Truran has included some color photos of zinc ore under the dazzling effects of ultraviolet light. But in particular, Chapter 9 titled “Strengthening America” portrays a long-gone America that benefited so mu ch from zinc mining. Truran said that copies of his new book are available for purchase at both the Franklin Mineral and Sterling Hill museums, as well as the Franklin Historical Society Museum on Main Street the same building that once served as a time office for the New Jersey Zinc Co. So, with three valuable books now to his credit, are there plans for any more Truran works? “Uh, yes,” responded the author modestly.