R-R-R-Read: Local educators sound out the balance that gets kids into books

READING. A post-pandemic drop in reading scores revs up science-based teaching while also leaving room for the magic of books.

Maybe you’ve been confused by the debate over reading scores raging since the pandemic. One side says teaching the sounds of letters is the way to get kids reading. The other believes fostering a love of language is the way to go. One is science-based; the other gives its nod to the arts and culture. Both methods sound pretty good. So why the reading war?

“While this has been a hot topic, this is nothing new,” said Meghan McGourty, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction at Warwick Valley Central School District in New York. But, she added, “People are more aware now, after the pandemic.”

Alisa Kadus started teaching 25 years ago and spent the last 10 as literacy coach for Warwick Valley. Science-based reading instruction goes way back, she said. In 1986, the psychologists Philip Gough and William Tunmer came up with a theory, called the simple view of reading, that had its own scientific formula. Kadus said it’s about a student’s ability to sound-out — or decode — written words while also understanding their meaning just as well as if the words had been spoken aloud. The effectiveness of this approach, she said, “is indisputable at this point.”

All of the educators we spoke to for this story agreed. “Explicit, systematic phonics instruction that is grounded in the science of reading should be the foundational approach,” said Marie Parisi, reading specialist with the Sparta Township School District in New Jersey. These foundational reading skills must be taught as early as pre-kindergarten, she said.

Three reading specialists from the Delaware Valley School District in Pike County, Pa. — Kristine Cottone, Jennifer Mulberger, and Elina Ramella – have a combined 66 years of experience teaching in the district. They say “whole language”– a complex approach that avoids phonics and immerses students in high-quality literature – is simply not enough: “Whole language can work for some students, but usually these students show gaps in their decoding and encoding skills because they are unfamiliar with syllable types, spelling rules, and generalizations.” They said the scientific research shows that a “structured literacy” approach, which includes phonics education, will work for all students.

Critics of phonics education say it’s boring and a turn-off. But local teachers counter that the magic of books is open only to those with solid reading skills. Matthew Kravitz, assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction for grades K-5 at Monroe-Woodbury Central School District in Monroe, N.Y., compared the process to becoming a good basketball player. He said, “The more you practice, the better you get, the more you want to play” – or read. Books are no fun if reading is never mastered.

Is it the pandemic?

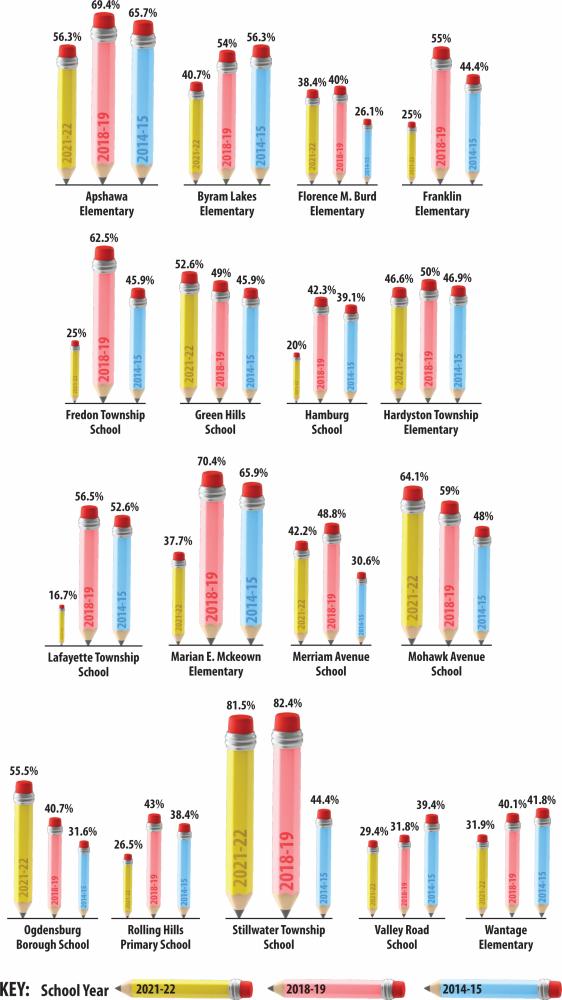

The controversy has arisen anew after a spate of recent studies found that as many as one-third of students in the early grades are falling behind in reading, putting into jeopardy the continuance of their education and success in life. The decline in reading scores nationwide began before the pandemic, but the dip since has been dramatic in some cases. In Sussex County, N.J., most schools saw third-grade reading scores drop in 2022, some by as much as 20 to 50 percent.

But not all local schools suffered the same fate. Some schools in Orange County, N.Y., saw third-grade reading scores improve, and significantly in a few cases. The Delaware Valley schools in Pike County, Pa., saw only slight declines across the elementary grades.

Kravitz, of Monroe-Woodbury, said he doesn’t know whether the drop in scores was all pandemic-related. “The situation was already hard, and that gap may have widened a bit,” he said.

Whatever the cause, the stakes are high. Children who fall behind in the early grades are on track to drop out of high school, according to the 2010 Annie E. Casey Foundation report “Early warning! Why reading by the third grade matters.” Any student reading below grade level once they hit the fourth grade will be unable to understand up to half of the curriculum, the report says.

Jessica Rostami, a literacy coach for the Vernon Township School District said “every grade level is important in the journey of reading. However, there is a large body of research indicating that children who have not developed reading proficiency by the end of third-grade will face far greater academic struggles than proficient readers.”

She said that while K-2 education focuses on phonics and comprehension strategies, in grades 3 through 5 “some students are ready to shift from learning to read to reading to learn, while other students still need a prominent focus on learning to read.”

For all the talk of missed benchmarks, local teachers do not see any point where students are beyond help. Rostami said, “We are seeing an increased need to continue foundational reading classes in upper grades that provide time with reading experts to close the gaps.”

“It is truly inspiring to help middle school and high school students who did not master these concepts in elementary school for a variety of reasons,” she continued. “

Some students do need to put in a great deal of effort when learning to read, said Parisi, of Sparta. ‘Sometimes children think they are not smart because they can’t read, and we remind them that some of the smartest people such as Einstein and Charles Schwab had trouble reading.”

The Delaware Valley teachers — Cottone, Mulberger, and Ramella, say their greatest challenge is the time it takes to implement a structured literacy program. “Many want to pick the apple, but we just planted the seeds,” they said. “It takes time and consistency to implement and see results. Our curriculum is rigorous, which is great for most students. However, our struggling readers have a difficult time keeping up with the curriculum. During reading intervention, we meet struggling readers where they are. However, in the classroom, they are still expected to complete grade-level assessments. These students will become overwhelmed and frustrated because they cannot keep up with the demands of the classroom curriculum.”

Or is ‘whole language’ to blame?

The controversy has arisen anew after a spate of recent studies found that as many as one-third of students in the early grades are falling behind in reading, putting into jeopardy the continuance of their education and success in life. The decline in reading scores nationwide began before the pandemic, but the dip since has been dramatic in some cases. In Sussex County, N.J., most schools saw third-grade reading scores drop in 2022, some by as much as 20 to 50 percent.

But not all local schools suffered the same fate. Some schools in Orange County, N.Y., saw third-grade reading scores improve, and significantly in a few cases. The Delaware Valley schools in Pike County, Pa., saw only slight declines across the elementary grades.

Kravitz, of Monroe-Woodbury, first noticed the public’s heightened awareness of the reading debate when his phone first “started blowing up,” mostly by acquaintances curious to know his thoughts after listening to the podcast series Sold a Story. The podcast is not a friend of whole language. As the introduction explains: “Millions of kids can’t read well. Scientists have known for decades how children learn to read but many schools are ignoring the research. They buy teacher training and books that are rooted in a disproven idea.”

Kravitz understands the emotion underlying the controversy. “Teaching kids to read is one of the single greatest gifts a teacher can give,” he said. “People are very passionate about how they do that.” And the phonics vs. whole language controversy “created some self-doubt among teachers. They said, ‘I got into this to help kids and maybe I didn’t help as much as I could have.’”

Last year, Monroe-Woodbury’s K-2 teachers told Kravitz they needed something more foundational for their reading lessons. “As a school district we decided to give them the resources,” he said.

What has been discredited in all this is the idea that students learn from guessing the words in picture books. “I’ve never heard that — a teacher pointing to a picture in a book and asking, ‘Guess what that is?’” said Kadus, of Warwick. What if the book says the picture is of a “sofa” but the student answers “coach”? How does that help?

Getting the balance right

Children in the first half of the 20th century learned how to read with the Dick and Jane books. “They are ‘decoders,’” Kadus said of the Dick and Janes, meaning that, while they include pictures on every page, they are designed for sounding out words. Kravitz noted that those early primers grouped words with similar sounds on a page, like run and fun, which reinforces those sounds and makes recognizable similar words the student may encounter later, like sun and bun.

But the Dick and Jane books are pretty dry, Kadus said. (And nobody ever read one under the covers with a flashlight.) There are infinitely more attractive choices now. “Many publishers have put out lovely decodables, with plots, character development, and beautiful art,” Kadus said. In the last few years, she said, Warwick has been ordering more of these enticing books. They are especially useful in kindergarten, she said, but at a certain point — different for every child — students must move past them.

“The most important part in every grade level is to nurture a love of reading,” said Rostami, of Vernon. “If students don’t read for enjoyment, no amount of phonics or comprehension instruction will be effective.”

Consistency and community

The educators agree it’s important to be consistent from school to school, classroom to classroom. “Expectations should be the same for every kid,” Kadus said. She and McGourty depend on teachers sharing their classroom experiences, going over what works and what doesn’t, as the curriculum is continually refined.

And all the educators said family and community are essential to childhood literacy. Parents can make a big difference by reading to their children at home.

Kadus recommends books written in a series, which reduces a young readers’ cognitive load in understanding characters because the same characters appear in each book.

Rostami said kids should have available to them a buffet of reading materials they love, whether “comics, Manga, graphic novels, others like poetry or historical fiction, or nonfiction.”

Another point of agreement among reading teachers? The kick they get out of seeing their students’ faces light up with new understanding. “The greatest joy of teaching reading is when children have that ‘Aha’ moment and beam with pride because they have read a word that was challenging for them,” Parisi said. “It is incredibly heartwarming to see kids curl up with books on the carpet and get lost in the story.”

“No matter how old children get,” Rostami said, “reading to them and with them is so powerful. Read to little babies, read to elementary-age children, read to and read with older students. Just read!”